Explorable Explanations:

The St. Petersburg Paradox

This paradox describes a theoretical lottery game which results in a random variable with infinite expected value but nevertheless would be of only small value to participants.

"A casino offers a game of chance for a single player in which a fair coin is tossed at each stage. The initial stake starts at 2 dollars and is doubled every time heads appears. The first time tails appears, the game ends and the player wins whatever is in the pot. Thus the player wins 2 dollars if tails appears on the first toss, 4 dollars if heads appears on the first toss and tails on the second, 8 dollars if heads appears on the first two tosses and tails on the third, and so on. What would be a fair price to pay the casino for entering the game?"

- Wikipedia, The St. Petersburg Paradox

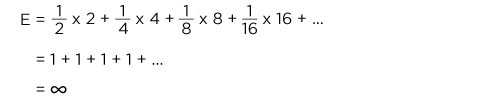

Ideally, the price to enter the game should be determined by the average payout of the game. The expected value is:

Assuming the game can continue as long as the coin toss results in heads and in particular that the casino has unlimited resources, this sum is unbound and so the expected win for repeated play is an infinite amount of money. Considering nothing but the expected value of the net change in one's monetary wealth, one should therefore play the game at any price if offered the opportunity. However, people should not be willing to pay more than a very small amount of money.

Why?

To figure that out, let's simulate some games to see what the likely outcomes really are.

Simulate games

games

drag

Total Payoff: $

Avg. Payoff: $

Since most of the time payoffs are very low, and high payoffs are incredibly rare, it does make sense not to pay a large amount of money to play this game. This leads to question: how do you resolve this paradox?

The classical resolution of this paradox involved the explicit introduction of the uility function (where, utility is the satisfaction or benefit derived by consuming a product) which presumes the law of diminishing marginal utility of money. According to this, the first unit of gain in money yields more uility than the second and subsequent units.

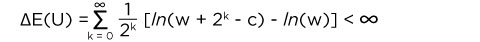

For this game, the utility model uses the logarithmic function, which is known as the log utility. In this function, the gambler's wealth is represented as w and the cost to enter the game is c. The utility function calculates the change in utility as ln(wealth after the game) - ln(wealth before the game), which is weighted by the probability of that event occuring. This value is definitely finite.

Utility is often used to show how a person should behave in such a situation. Let's try to predict how a person should behave according to Utility theory by taking into account both the Wealth of the person, and the Cost to play the game.

Simulate games

Wealth: $

drag

Cost: $

drag

You should be willing to play

Ideally, you would look to maximize your utility. Hence, in any game where your payoff is less than zero you incur a negative utility. Under the current constraints, you should be willing to pay a maximum of to enter the game, as the equation above indicates, the summation from 0 to infinity yields a positive value if the cost is atmost $8.